What if the Fantastic Four turned bad? We’ll come back to

this…

Planetary is a comic series published by Wildstorm comics

from 1998 to late 1999. Despite that lengthy period it consists of only

twenty-seven regular issues, three crossover issues and an introductory short.

It was written by Warren Ellis, drawn by John Cassaday and coloured by Laura

Martin. It’s set in the Wildstorm Universe (which has since been assimilated

into the DC Universe) but in actuality has very little to do with the company’s

established characters or titles. It’s a thematic successor to Ellis’s run on

Stormwatch and The Authority.

The series focuses on the Planetary field team. Comprised

of Elijah Snow, a man who can subtract heat form the atmosphere, Jakita Wagner,

a woman blessed with super strength, and The Drummer, who has complete control

over all technology, they’re tasked with uncovering the secret history of their

world. That sounds a little broad, and it is. It’s basically the creative team’s

excuse for the team getting involved in the plots they do. They have unlimited

resources and answer only to the mysterious Fourth Man, the identity of whom

becomes one of first of many mysteries in the series.

This is a completely accurate summary but it also fails

to do Planetary justice. There’s so much more to the title.

The central conceit of Planetary is Ellis’s use of

history to create a world of wonder. There’s an ongoing plot threat and a few

loose arcs but all but two of the issues are self-contained stories (the two

that aren’t are a two part story). This allows Ellis much more creative freedom

than the traditional approach does. There’s no regular base or lengthy,

convoluted explanations about how bad guys that were definitely killed last

time we saw them are able to return.

Ellis makes use of a number of literary sources for

Planetary. Issue two, for example, draws heavily on the tradition of Japanese

monster movies. Issue eight is a cross between Cold War paranoia and fifties B

movies. Australian creation myths are the basis of much of issue fifteen,

although John Carter of Mars is also a source of inspiration for that issue.

That should hint at how broad the series can be even within one issue. Action

movies, Sherlock Holmes, The (Steed and Peel) Avengers, Norse mythology, and

the X Files all provide ideas for Ellis at various points too. It’s an eclectic

mixture of literature, pop culture, TV shows, and, of course, comic book history.

It sounds incredibly busy but it’s all perfectly judged,

the sources never overshadow the central plot or the characters Ellis has

created. Ellis uses the fiction we’re all familiar with as a storytelling

shorthand. It’s a little like Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen,

only broader in its reach and less focused on using the sources it uses as the

centre point of its tale.

And I’ve yet to mention the comic book sources Ellis

draws from. Throughout the series characters appear that are clearly based on

characters from Marvel and DC, names changed partly because of legal reasons

and partly because Ellis presents them, to a greater or lesser extent, as

alternate versions of those established characters. He’s more interested in

subverting the known aspects of the characters than the characters themselves,

which is a healthy approach to take. We see Nick Fury, Captain Marvel, John

Constatine, and Spider Jerusalem reimagined, and the work of several comic book

greats referenced, most obviously and frequently Jack Kirby.

And then there are The Four. They’re the Fantastic Four

done as though they were bad guys. The starting point for the idea was an issue

Ellis has with the Marvel version of the group: they have great powers,

resources and inventions but use them only to fight bad guys. There’s no

attempt from the group to better mankind. That becomes a central idea of Ellis’s

Four.

We see them slaughter the population of an entire planet

just so they have somewhere to store their immense weapons collection. We discover

that they created they internet (although it’s never actually revealed why). Most notably we see them eliminate

Wildstorm versions of Superman, Wonder Woman and Green Lantern before they can

have any positive influence on Earth. And none of this is done for the sake of

it. By the time Planetary finishes we know exactly what motivated The Four and

how and why they’ve done what they’ve done.

Understanding all of this in relation to the source

material is obviously fun and adds another level on which to enjoy the book. If

you don’t recognise something enough to know what the source material was you stil

follow what’s going on within the context of the tale. You aren’t isolated

because of ignorance but knowledge and understanding of pop culture and comic

books specifically is rewarded.

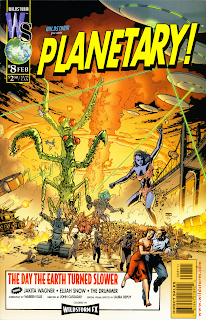

I would like to add that the creativity is not limited to

the stories told within Planetary. The covers are an integral part of the

book’s experience, mirroring as they do the chief themes and inspirations of

their contents (see the selection posted at the top of this review. Issue 23,

for example, is the pulp heroes story, its cover done up to emulate a cheap

disposable paperback from the thirties. The John Constantine issue perfectly

replicates the original style of Vertigo titles. Meanwhile issue fifteen evokes

ancient Australasian tribe art. The covers alone contribute more to the stories

Ellis and Cassaday tell than most authors pack into twenty-plus page issues.

Cassaday’s artwork is just as important to the book’s

success as Ellis’s writing. A lesser artist (and there are many) would have

been incapable of transferring Ellis’s more outlandish ideas to the page. There

are few artists who could have produced work that was one moment awe inspiring

and the next detailing the unspoken emotions of an office drone. Cassaday

perfectly captures The Drummer’s neuroses and skittishness, Jakita’s confident

swagger (just look at the perfect panel at the bottom of issue eight’s twelfth

page), and Elijah’s deliberate pondering. In lesser hands this could have

become just another superhero book. Cassaday helps it to become something

incredibly special.

The links to the Wildstorm Universe start out infrequent

and vague and are pretty much gone by the halfway point of the series. That’s

no bad thing. Ellis does more to create a cohesive history for this fictional

universe in Planetary than everyone else had done combined. Instead of trying

to make everything tie together he focuses on threads he’d started up in other

books. Such as the century babies.

Anyone who’s read The Authority will be familiar with the

idea of a group of people with special powers sharing the birthday of January 1st

1900. That’s elaborated on in Planetary, although ultimately we’re left with

more answers than questions on the topic. The concept could very easily support

a comic series in its own right. It’s a testament to Ellis as a writer that he

hasn’t ruined the mysterious air he worked hard to cultivate by taking on such

a project. The idea works best when used as an unresolved thread in the

background.

With Planetary Ellis wanted to reintroduce wonder and

discovery into comics, something he (rightly) felt had disappeared from comics

throughout the course of the late eighties and the nineties. He essentially

writes Planetary as a creator owned title and uses the Wildstorm Universe as

little more than a backdrop. It’s not something that could have been done with

the continuity heavy worlds of Marvel or DC. It works here because Wildstorm is

(or was now, I suppose) so much younger as a company. Ellis gave it an identity

of its own with this title, and wrote a series that will be enjoyed for a very

long time. You could not hope for a more inventive comic.

No comments:

Post a Comment